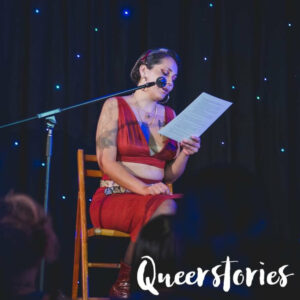

Hi, I’m Maeve Marsden and you’re listening to Queerstories.

This episode was recorded in partnership with Byron Writers Festival. I was meant to be hosting a live event up north but due to Covid restrictions that obviously couldn’t happen. However, with support from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund, we recorded a very special Byron Writers Festival Queerstories podcast. And you can enjoy the whole thing as part of their Conversations From Byron series at byronwritersfestival.com or you can listen to the stories one at a time here.

Ellen van Neerven is an award-winning writer, editor and educator of Mununjali, Yugambeh and Dutch heritage with strong ancestral ties to South East Queensland. They write fiction, poetry and non-fiction, and play football on unceded Turrbal and Yuggera land. Ellen’s books, Heat and Light, Comfort Food and most recently Throat have won countless awards, and they’ve edited three collections, including the recent Homeland Calling.

Ellen

Jingeri jimbelung [hello in Yugambeh].

I’m on Yuggera and Turrbal jagun and I’m Mununjali from the Yugambeh language group, which for those of you who don’t know, is the Logan, Gold Coast and Scenic Rim region of Southeast Queensland.

My mum is a Currie and a Williams, we have a really big family here in Brisbane, and my dad is Dutch – the van Neervens are also a really big family that come from a village called Mierlo in the south of the Netherlands.

I’m going to read to you five poems from my new book called Throat, and I’m just going to give you a little bit of context to the book which was written over a four-year period. Two of those years I spent in Naarm on Kulin country and the other two were back home on Yuggera and Turrbal country in Brisbane.

I had some amazing experiences in Naarm but I felt quite homesick and I had a tendency to be hard on myself. Whenever I felt depressed or homesick, I thought about my spiritual connection to Country and how nothing can ever take that away, because it’s inside of me. I thought about the rivers, particularly Maiwar, Brisbane River, and I thought about the mountain ridge out Beaudesert way, I thought about the storms and winds and rains and the earth and the trees and the birds, and I found my way back.

The title of Throat comes from a quote from the Black British poet Patience Agbabi. I love Throat as a title because it can symbolise more than just one thing. Throat can be like your power to speak, throat can be about pleasure, throat can be about pain, and I was also thinking about the black-throated finch which has been a symbol for the fight against the Adani Carmichael coal mine. It’s a beautiful bird which is already endangered and has already lost 88% of its historical range. It’s that threat that’s constantly there. Environmental themes, I write about these strongly because if Country is not healthy, we are not healthy.

This book has five sections which is really important to sort of note. The first section is called ‘they haunt-walk in’. Now I’m sort of taking cues from two writers, Qwo-Li Driskill, who’s a Cherokee Two-Spirit writer that talks a lot about haunting, and Blood Memory which is inspired by Natalie Harkin which those of you will know is a queer Narungga writer from South Australia. Ancestral memory is what I really draw in in this particular section and just how present it is in our bodies, and how memory can be both comforting and painful.

I’m going to read you a poem called ‘Vinegar’. This poem refers to cleaning as a sort of site of violence for racialised people.

Vinegar

Sometimes, the house is unclean.

In this panic

I find myself in both past and future.

When we clean houses we do so knowing that they are watching

and our lives depend on it.

When we teach our children to clean houses we do so knowing

that they are watching and our lives depend on it.

I honour your cleaning recipes. Squatting on the shower floor.

I will not have to work as hard and I don’t have your

burdens but I wonder

does the intergenerational load get heavier or lighter?

That was ‘Vinegar’.

Section two is called ‘Whiteness is always approaching’ and it’s informed by Claudia Rankin’s work who is an African-American writer. And she writes: ‘How do you understand white privilege if you don’t understand that you’re white, if you don’t understand that racism is actually about how whiteness functions inside the culture?’

So often us as First Nations peoples and I think Claudia’s talking about Black people in American and other racialised groups like First Nations Americans, we are studied and we are pulled apart but what critical race studies is doing is sort of turning it upside-down and looking at whiteness, looking at white supremacy, white privilege, white guilt, and I wrote some of this section when I was in Europe and saw how extractive colonialism made Europe what it is today. And I wrote this poem while I was in this really extravagant pool in Munich, in Germany. And just thinking about the kind of wealth that had been stolen to build a building like this.

The body labours under memory

My tongue hurts

from all the things I have said

all the things I haven’t

Ways of feeling invisible

require

proper planning

All the spit in the world

in this pool

especially mine

The third section, ‘I can’t wait to meet my future genders’, talks about gender as a colonial construct. I really see my gender as fluid and I embrace that, I celebrate that, but there have definitely been periods of confusion and I wrote this poem, ‘Dysphoria’, when I was feeling kind of like an alien in my own body, feeling like I wasn’t good enough, I wasn’t one or the other and that made me feel kinda weird. And of course being in relationships, you have to negotiate your body with another person and that can be quite triggering.

Dysphoria

liberate love

into dust

shifting, self-gearing

love them all

credit me

do what makes you happy, she says

but doesn’t mean it in the way my mum says

the desire to take clothes off

to take them off but also take

off another level underneath

peel away those expectations

get closer to my truth

I love my mind but I haven’t come to terms with this

I catch you in an embrace with another part of me

looking backwards

into dust

The fourth section ‘speaking outside’ is like a bit of a riff by Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde who’s one of my favourite writers. Lorde was writing about intersectionality way before it became the buzzword that it is today. I’ve got this book of essays that come from Sister Outsider and some of them of them are really seminal like ‘Poetry is not a luxury’, ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’, but my favourite is called ‘The uses of the erotic – the erotic as power’ which explains erotic as not just a physical experience but a sort of magic, a show of resilience in the face of racist, patriarchal and homophobic society, and Lorde said, ‘When I speak of the erotic then, I speak of it as an assertion of life force of women, of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work and our lives.’ So this section is really about reclaiming our language as someone who has the kind of birthright of wanting to learn Yugambeh language, language that’s been stolen from us but still we hang onto. I was part of a project where I worked with my cousin Shaun Davis to work on some translations of my poems which are included in this section, and while I was learning language and going on this journey, I wrote this poem which is called ‘I do have a tongue’. And it goes, ‘I do have a tongue that wants to speak in the language of cultural desire.’ And that’s really about me having these desires that are beyond empire, that are actually really innate to me as a spiritual Yugambeh person who has this inside me, the need to connect and the need to be autonomous.

I do have a tongue

that wants to speak

in the language of cultural desire

I want so much more

Which part

brain body throat

does language enter?

Tell me what happened at the opening

What does it mean to be held

in another

tongue

The tongue leads us to the last section of my book, which is called ‘take me to the back of my throat’. Saying take me to that dark, vulnerable place, I’m ready for it, I’m ready to tell you all my secrets. Honouring and truth telling. And saying that if you want to come on this journey with me and be vulnerable with me as a reader, I have to be vulnerable as a writer too. So this is a very small poem. It simply goes:

take me to the back of yr throat

I’ll stay

take me to the back of my throat

I’ll stay

Maeve

Thanks for listening. Please rate, review, and subscribe to the podcast, and follow Queerstories on Facebook for updates.