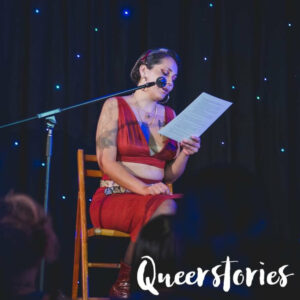

Maeve: Hi, I’m Maeve Marsden and you’re listening to Queerstories. This week, Lara Thoms is interested in socially engaged, site-specific and participatory possibilities in contemporary art and performance. She works as an artist in Field Theory and is a co-director of Aphids. For ten years she has also been a curator and producer for organistations including Dark Mofo, Supplefox, Next Wave and Performance Space. Her work has been presented with Perth International Arts Festival, Artshouse, Gertrude Contemporary, The Malthouse, Next Wave festival, the MCA, Performance Space, Radial System v Berlin, as well as multiple venues and institutions.

Thank you, that was a pretty special time when we were fifteen. I will say I was quite a cocky teenager, and at one point ‘A Current Affair’ invited me to debate Pauline Hansen on television. I was so up for it and then she pulled out an hour before. So I’m going to tell you about a party that I organised.

I am at my very first day at an arts festival and I am staring into a warm cremation chamber.This is not an installation. An hour or so ago it had an ‘old mate’ inside. I am introduced to this machine as the ‘Big Scone Cooker’, by a funeral director called Scott, who clearly likes a joke.

I am here because I have been asked to create a party in this active funeral parlour. Not a wake for someone I knew, but a lavish costume ball for 700 people who have a penchant for dark art, or at least cash to burn. Hint, I’m in Hobart. The $90 tickets for the event sold out months ago.

Scott is actually quite serious about his profession, and he’s run a very successful family business for several generations with the tagline ‘Every Goodbye is Different.’ His interest is in developing the death industry to have more imaginative options, but most of his business is still in classic beige services.

He is dressed up in a waistcoat, and offering me beer. We are talking about how stained his carpets might get after the party, and I mentally put aside hundreds of dollars for steam cleaning. It might be the heat of the crematorium, but we’re warming to each other. He has the humour and tone of someone in high school, which he didn’t finish, but with that knack of fitting very deep wisdom into an average chat. He explains that while the party could turn off some of the more conservative funeral customers it might pay off when the younger generation starts to croak.

Unbeknownst to my employers, I have actually organised two funeral parties before – my mother’s and father’s. Actually my dad really organised them, because despite being labeled a hippy he was a meticulous organiser. He made sure everyone at my mothers wake had a turn on the microphone – an anti-hierarchical move which made it feel like an anarchist club meeting.

For the launch of his own memoir, Dad hired an ageing, surf-rock band, commissioned a 1970s-style light show, not a design a show, and ordered lot of whiskey. Despite all of his oxycontin-infused preparation, this party ended up being badly timed, booked for two weeks after his death, naturally became his wake and it ended with us dancing in colourful outfits and smoking joints under purple lights.

I hadn’t put these wakes on my resume, but, for a 32-year-old, I did have unlikely experience with crematoriums and catering for mourners. I quickly become soothed as Scott deepened my understanding of the machinations and quirks of the death industry that I had encountered in my twenties. Finally, here was someone who understood the banalities, bureaucracies and immensity of it all.

I go back to Scott’s parlour several times as preparations develop, I say its to refine the lighting plans but its mostly to find out about Scott. He shows me a product he has developed that is really just a postal tube, to allow ashes to come out quickly and smoothly, because “Urns are pretty awkward, you really can’t get all of that dust out its bum”.

I see the plastic bits he puts around the gums of dead people so that their mouths stay closed. I smell the lynx deodorant on the mortuary table, perhaps the generic smell of all Australian men? Each time I visit I hear about Scott building things like boats, and piers, and sheds inside his chapel, bringing in goats and tractors for passed away farmers, because “every goodbye is different”. He’s basically the installation artist of the funeral industry.

I get nervous about impressing David Walsh and Scott with the Gothic party. I ask my girlfriend Ellie to assist because I am bad at making decisions alone. She hunts for black lace and sends me photos of old keys and chandeliers. We don’t know how to stop the party from feeling like a crass Halloween house or a steampunk convention.

When Ellie visits the parlour she too warms to Scott. She asks if she can lie in a coffin, and he happily obliges. She looks pretty with her face surrounded by bunched satin. Scott reveals a custom made coffin, dropped off to his friend at a car detailing garage to be sprayed a sleek black. “You just can’t get em this shiny otherwise”.

I disappear and try to find art for the dark art party. An artist wants to make a mushroom suit replica enabling fungi to take over your rotting body – now known as the most sustainable form of corpse disposal. I talk to a 35-piece electro-marching band that wear balaclavas. I chat to caterers who want to make borsht, matched with vodka served in tear-droppers with tissues. The lighting designer visits and asks if she can lie on the electronic lifter that sends coffins upstairs. Again Scott obliges, and she slowly whizzes up on her back. We squeal in delight. This is better than six feet under.

Ellie and I start to argue, reeling from the tension about wanting to make a wildly memorable party and not disrespect the sensitivity of the site. She gathers vines from the side of the road and spray-paints them black. We have arguments about how cheesy LED candles really are. And then, as I am walking around a car park about to buy waffles from a food-truck, I see her in the distance, noticing her wet face. “My mummy died,” she says quietly.

We want to call Scott, and then we remember bodies can’t travel interstate. We have a bath and eat spaghetti and cry and then go on a 6am flight to Canberra.

Her mother’s death was both unexpected and the result of a 12 year battle with cancer. In Canberra, Ellie struggles with the local funeral directors who are definitely not Scott. They suggest that everyone drink from plastic cups so they don’t have to do the washing up. She visits sites for the service that are just not cinematic enough, the room’s lack warmth, she thinks her family lacks imagination. I think that she might be beginning to mix up our funeral party with her mum’s service. I remind her that there are four family members in the mix, and that her mum actually quite liked religion. She cleans and cooks for her forty cousins to deal with her frustrations.

I have to fly back to Tasmania, as my own funeral party is in 24 hours. Everything is behind, I am missing the only person who shares my vision, but I am strangely calm. The death before the party has of course made the event seem much less important and I feel numb not being with Ellie. She insisted I leave, knowing the event would be impossible otherwise. I take solace in the fact I spent intimate time with her family, viewing her mum’s body, an affair I tell myself is as important as the funeral I’m about to miss.

While Ellie writes her eulogy, I set up a tombstone with the date of the party engraved on the front. While she books catering, I change light globes from red and order dry ice. Scott speaks about a big gap that has been created in her absence as we move coffins, flowers, video art and mirrors around his workplace. She demands I send her photos and updates as we simultaneously design sorrow and celebration in separate cities.

Everyone arrives at Scotts place dressed up and excited. They’re wearing ugly top hats, because the steampunk vibe did rear its head. There’s rams horns, there’s lacy skirts, champagne flows, DJ plays tracks punters pre-nominated as their own funeral songs. Upstairs performance artists create intimate reflections on death and dying.

In one room an artist slowly prepares nude bodies, covering them in bejewelled white shrouds. The mushroom suit glows, a record is played with a real person’s ashes encased in the clear vinyl. The marching band begins to crowd surf. I expect to feel demoralised, or disgusted by the superficiality of it all, but I don’t. Being a smallish town, dozens of attendees tell me they have been in this space for recently departed grandmothers. They talk about the transformative affect of considering death in another way.

“This space feels so different tonight! I want to got out like this!” A woman says, bush in hand.

I agree that the taboo of death feels broken down, and with that a space to be less scared and more open about our end of life decisions. Scott is a big part of this feeling. He hosts people melting marshmallows on the crematorium fire while inviting them to ask him anything they like about death.

Industrial beats boom while Ellie’s spray-painted vines hang above a packed dance floor. I wear a walkie-talkie and move from space to space in a sober haze. At the same time, Ellie and her aunts sit at her family dining table lit by the lounge room fire. They are carefully weaving together fresh autumn leaves to create a backdrop for the Canberra chapel. They will carefully hang it behind her mother’s coffin the next dat while I throw away beer stained carnations that have been crushed on the dance floor.

Thank you