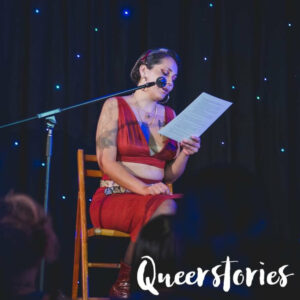

Maeve: Hi, I’m Maeve Marsden and you’re listening to Queerstories. This week Josephine Inkpin is the first openly and fully recognised transgender Anglican priest in Australia, now currently working as Minister of Pitt Street Uniting Church in Sydney. Chair of Equal Voices, the national network of LGBTIQ+ Christians and allies, Jo has also been a prominent leader in inter-faith, multicultural, Reconciliation and other justice activities over many years. Originally from England, and later described as a ‘Dangerous Woman of Queensland’, she lives with her wife Penny and shares the joy of children and grandchildren. This story was performed in June 2021 at Giant Dwarf in Sydney, just before the Delta COVID outbreak and the long lockdown that came with it. Giant Dwarf, the venue didn’t survive this final straw after 18 months of lockdowns and pandemic mayhem. Queerstories wouldn’t be what it is without Giant Dwarf. The venue where in 2017 I started monthly events, quickly selling out every time. It was also Giant Dwarf who first produced this podcast. The loss of that space is a real loss for me and for Sydney’s art and entertainment scene. It’s bittersweet sharing these wonderful stories from that last event but great to hear the audience once more. Enjoy.

Jo:

I‘m not precisely sure when I discovered that God and religion are queer, but it certainly involved Sunday School. What a name eh? The words ‘Sunday’ and ‘School’ don’t sit easily, do they? These days Churches tend to look for alternative ways of providing children’s faith education. When I was growing up however ‘Sunday School’ was pretty much all we had. In rural areas especially, you could either be bored to tears on Sunday afternoon, or you could go to Sunday School. Sabbatarianism reigned – very oddly: for you’d think what was originally called ‘the day of resurrection’ would be particularly joyous. Happily, during my English childhood, God started changing her mind about repression. Sadly some Christians are still catching up. Thanks to the energy crises and industrial unrest of the 1970s, we struggled to do the usual things in the working week: rugged up as we were with candles against the cold and power cuts. So Sundays started to be freed up. The results included the rise of Margaret Thatcher and her rabid capitalism. It also saw the death of traditional Sunday Schools, and, for a while, my meeting with queer divinity.

Now I don’t know exactly what others gained from Sunday School. Apart from being able to mess about with friends on otherwise dour Sundays, I only really remember two things. The first was the stamp. For if you didn’t play up too much, you received a sticky backed, serrated edged, images of Bible, or other Christian, characters. Bereft of later electronic and other entertainments, this was quite something. We kids were used to collecting stamps, depending on our gender, of footballers or ballet dancers, trucks or flowers, or a mix of all. Companies produced them to sell their wares, not least in cereal packets. The Sunday School stamp however was always different. You could never tell what you were going to get. Rather like religion as a whole – some days it could be incredibly banal, moralistic, or insulting to the intelligence; on others it could open doors to amazement and changed perspective. Like the recent church signboard proclaiming the ‘best way to heaven is on your knees’ – some stamps were unwitting visual double entendres or images beyond the conventional: near naked male saints embracing in divine love; fabulous queens of heaven and other extraordinary beautiful and bold women portrayed in daring contexts; eunuchs, gender fluid heroes and angels, and Jesus themself – they of official ‘two natures’ and very queer birth and lifestyle. ‘Come, Jesus, come’, we were encouraged to pray…

Like the furtive moments of dressing in my mothers’ clothes, dousing myself in her perfume, and toppling over in her heels, the Sunday School stamp was sometimes a whiff of freedom in my early years. Nothing however was such a splendid Sunday School gift as the pantomime.

Each year, again if you hadn’t played up too much, we were packed into an overcrowded raucous and rickety bus and taken to an annual pantomime in Lincoln – to us the big city. Where I grew up, this was a big deal. For our little town may have been in England but it was metaphorically in Dorothy’s Kansas. It does have the best small racecourse in the UK. Otherwise it is easily passed by. Charles Dickens visited once and recorded that you could fire a cannon down the main road on a Saturday night and not hit anyone. It is still largely true. Not for nothing perhaps is the town recorded in the ominous sounding Domesday Book. The highlight of my youth was thus the visit of Elton John, who, like Robert Menzies’ Queen, ‘we did but see her passing by’, albeit as a much more exciting queen. For our town’s other claim to fame was that, like me, Elton John’s friend and lyricist Bernie Taupin grew up nearby and went to school there. His main tribute to the town was Elton John’s Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting, which pretty much says it all for entertainment possibilities!

The Sunday School pantomime trip was therefore always a truly wonderful outing. Today, it may seem very tame, but to me, skipping up the Theatre Royal steps was like entering a piece of heaven. With its décor and delights, it was a gorgeous feast for this queer sensate starved child. I loved – I still love – heavenly staircases, down which beautiful dresses don’t just flow but float. Gold seemed to glisten everywhere, on doors, balustrades and in glittering eyes and costumes. Fabulous faces from the theatre world hung on the walls at every turn – full of extraordinary energy, diversity, and invitation. Even the bathrooms oozed class and style – until a hundred Sunday School children had done their worst!

Best of all was the stage, which turned so much upside down. For, like Shakespeare, at its best, English culture can reach to the sacred skies, but it is also incredibly, gloriously, profane. Such is pantomime. It is poor people’s theatre, with many British strengths and limitations. It can be stupid, raw and crude, but it has power to challenge and overturn expectations, and, like grander art, it has provided outlet for the queer. Looking back now, so much pantomime has been full of gender stereotype. Today I’d explode, rather than cringe as I did at times back then, at the gynophobia and transphobia that was redolent in many jokes. Like bad drag queens, the character of the pantomime dame can be shocking for gender diverse people. Yet, imagine the impact on me, as a little kid, when the first figure I ever saw on stage was an apparent ‘man in a dress’ and the next a Principal Boy who was actually a girl. You’re not quite in England’s Kansas anymore darling! Thanks then to the Church of England for showing me the Yellow Brick Road.

Now, to be quite honest, unlike my wife, I never wanted to be the Principal Boy, even less than I wanted to be the Pantomime Dame. Both are better than being the pantomime horse, certainly the back end – although who knows what goes on under the covers? But seriously… why wouldn’t I want to be Cinderella – with a fairy godmother, a stunning dress, attendants, and shoes that fit?! Who, like Aladdin, wouldn’t love rubbing lamps and other things that bring delights? After all, everyone should have a friendly genie in their life.

Sunday School gave me a taste of true magic: even with its conventionalities, the power of subversion and transformation. The little girl hidden in her assigned gender ashes could go to the ball. Things were not fixed, but could be transformed. It fitted with other things I learned as a Sunday School child, symbolised in the queerer stamps: that water can become wine; that queer people can walk on water; that joy is not only possible but very real – even, like Jesus, being covered in oil and pampered by a gorgeous woman. Sometimes, you know, I think that being a priest is like being the Wizard of Oz in the pantomime of life. All the religious songs and scenery, props and levers may not amount to much. Yet to those whose eyes are open, they can provide a stage, a road, on which we find our hearts, our minds, our courage, and our love. Maybe Sunday School wasn’t such a bad thing after all.

Maeve: Thanks for listening. Please subscribe to our podcast, share your favourite tales on socials and follow Queerstories on Facebook for updates. If you enjoy Queerstories, consider supporting the project on Patreon. Check out the link in the episode description. Finally, for late-night ramblings, gay shit and photos of me trying to garden with a baby on my back, follow Maeve Marsden on Twitter and Instagram.